The European Central Bank’s first meeting of the year is set to bring the formal launch of a strategy review, most likely including a rethink of an inflation goal the bank has failed to meet since 2013.

The scope and scale of the review is likely to be discussed and is a key focus for markets given the far-reaching implications for monetary policy.

A slightly brighter tone to data means the ECB’s assessment of the economic outlook will also be scrutinized on Thursday.

Here are five key questions on the radar for markets.

1. What details could we get on the strategic review?

The first review of ECB policy since 2003 could be formally launched on Thursday, with the structure, timeline and agenda, as well as a process that could last all year likely to be debated.

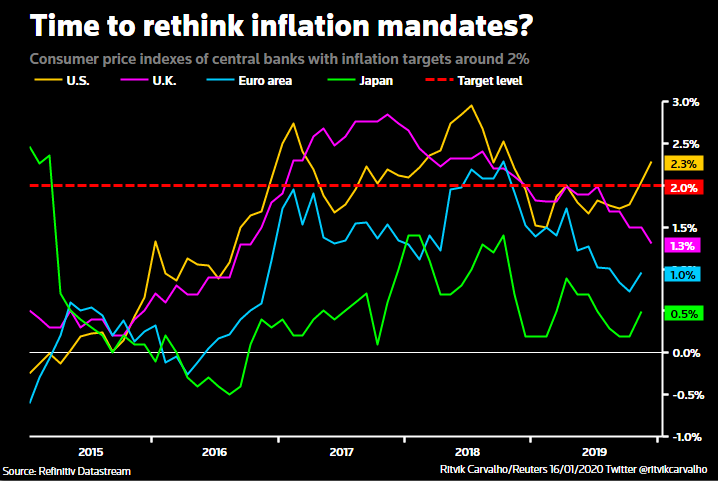

ECB chief Christine Lagarde says a key focus will be to determine whether the objective of keeping inflation near but below 2% remains valid, given changes in the global economy. It’s a debate other central banks with similar targets such as the U.S. Federal Reserve are having.

“The whole inflation goal will be the central point, there will be a variety of issues around this including how you define the goal,” said Nick Kounis, head of financial markets research at ABN Amro.

“There could be some signaling that they will look at the measure of inflation they target and there’s also discussion over whether they should discuss the policy tools available.”

For sure, policymakers are keen to shape the debate. The ECB should consider a clearer inflation target, newest ECB board member Isabel Schnabel said last week.

2. What can the ECB say about the economic outlook?

The ECB will be pressed on whether it thinks the worst is over for the economy and the implications for policy near term.

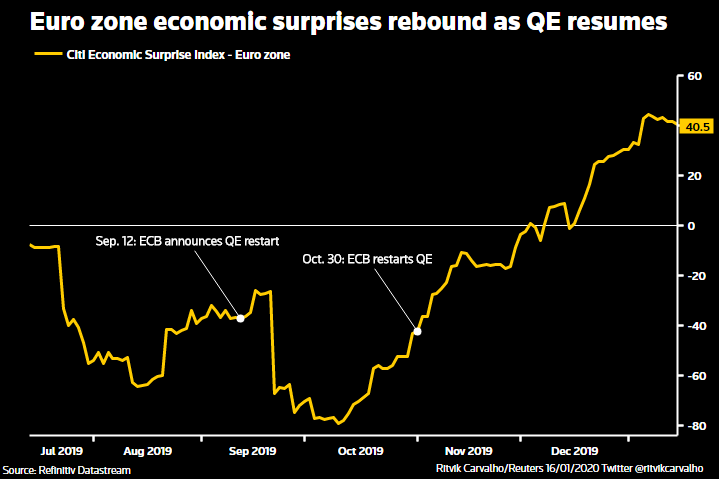

Key business activity data covering the manufacturing and services sector showed the bloc’s private sector growth reached a four-month high in December, and Citi’s economic surprise index is near its highest in almost two years CESIEUR. Nearly 80% of economists polled by Reuters on the bloc’s economic activity believe it has bottomed out.

The Phase 1 U.S./China trade deal has eased uncertainty in world markets, while euro zone investor morale is at its best level since the end of 2018.

Analysts say it’s too early for the bank to change its thinking. Adjusting its message too hastily could backfire if subsequent data releases don’t hold up. Minutes from the ECB’s December meeting noted that while the data is stabilizing, it remains weak.

“We just have to see the surveys…translate into hard data, which obviously takes time,” said Marchel Alexandrovich, European financial economist at Jefferies. “Realistically the ECB is on hold for at least six months before even sending any shifts in terms of potential future policy changes.”

3. Inflation is picking up, surely that’s good news?

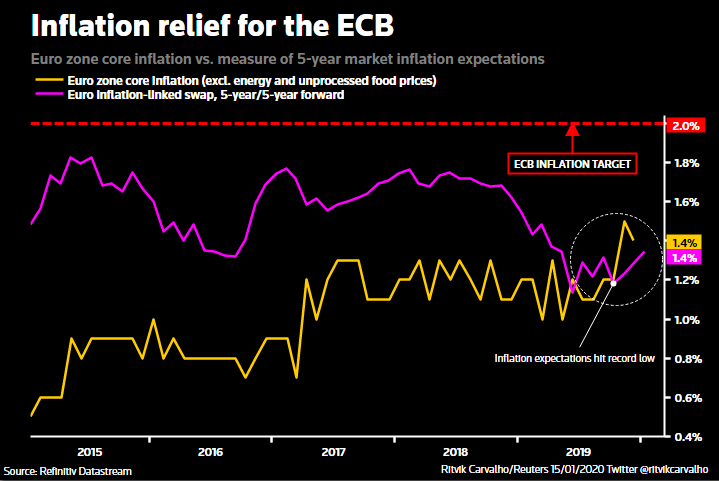

Euro zone inflation jumped in December, adding to a sense that the outlook is improving and that the ECB can afford to bide its time after delivering hefty stimulus in September.

After two solid readings of core inflation, which strips out food and energy costs, Lagarde may be asked if the ECB sees some more upside potential for inflation.

And a key long-term gauge of market inflation expectations is near six-month highs, recovering from record lows.

Still, the ECB’s December forecasts suggested inflation would undershoot its target even at the end of a three-year period, and economists say it’s too early to call a turnaround.

“As an economist, the biggest frustration is that we haven’t heard about Lagarde’s own convictions,” said Pictet Wealth Management strategist Frederik Ducrozet.

“We want to know what she really thinks about the inflation outlook having talked to colleagues.”

4. Sweden just ditched its negative interest rate policy. Could the ECB follow?

In December, the Riksbank ended five years of negative rates by raising borrowing costs to 0%, citing risks from keeping rates negative for too long. It became the first central bank to ditch the negative rate experiment, sparking speculation that the ECB could follow.

That’s added to a perception that the bar to further ECB easing is high and money markets are starting to price in higher interest rates in 2021.

Some policymakers are growing increasingly concerned about the unwanted side effects of negative rates on banks, insurers and pension funds among others. Still, the ECB has maintained that the benefits to the economy outweigh the negative costs. But more than three-quarters of economists polled on this question believed the ECB would keep rates negative this year.

And with bank lending surveys demonstrating some positive impact from negative rates and the recent uptick in bond yields beneficial to insurers, “the incentive for the ECB to act and to get rid of negative interest rates is weaker,” said Natixis’ head of research solutions Cyril Regnat.

5. What does tension in the Middle East mean for ECB policy?

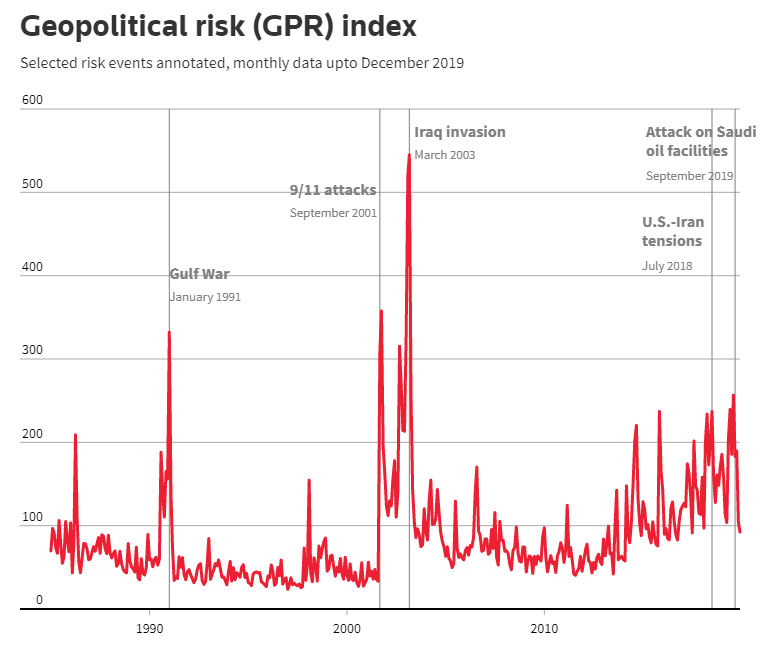

Concerns about trade wars and Brexit have ebbed, but U.S.-Iranian tensions have flared up, briefly triggering a surge in oil prices in January.

Lagarde, like her predecessors, may stress that geopolitical tensions are outside of the ECB’s control. Still, markets are keen to get a sense of the central bank policy response should the situation escalate, hurting the economy or triggering a sustained move up in oil prices.

The ECB has previously estimated that a 10% rise in oil prices has a gradual negative impact on GDP growth of 0.1 percentage points in the first year. At the very least, geopolitical tensions are likely to encourage the ECB to maintain an easy monetary policy stance, analysts said.